Consider a child who speaks the following phrase:

“Is not underhand over the post garden implications.”

In one sense, there is nothing ‘incorrect’ about it. All of the sounds, or ‘phonemes’ to use the jargon, are in the right order and everything has been pronounced accurately. But, of course, the phrase has no meaning and the child is therefore conveying no meaning whilst speaking it.

Speaking is clearly more than simply the rote regurgitation of ‘correct’ sounds.

At West Bay University, most of our education research involves finding out what pre-service teachers’ attitudes are to various aspects of education. We are not alone; this exercise dominates research across the field and with very good reason. We wish to discover whether pre-service teachers approach their vocation with constructive or destructive informal pedagogies; whether they believe in authentic, contextualised, real forms of learning or whether their own childhood experiences have locked them into paradigms of rote memorisation.

Our research into attitudes towards the teaching of speaking shows that many pre-service teachers haven’t even considered it! This shows the emphasis that society has previously placed on this crucial area – none! Here at the Extraordinary Learning Foundation™, our mission is to change all that.

Moving on from our first phrase – where meaning was clearly absent – I wish to now present a more complex and nuanced example. Imagine if a child in Grade 2 were to declare the following.

“Democracy is a good way to protect people’s freedom.”

What would you think now? You might be inclined to suppose that this child was ‘smart’. Yet, the work of the German psychologist Edmund Rotz shows us clearly that a child at this stage of development could not possibly associate appropriate meaning to such a phrase. In actuality, what we are witnessing is rote verbalisation without meaning. The child has no idea what she is saying.

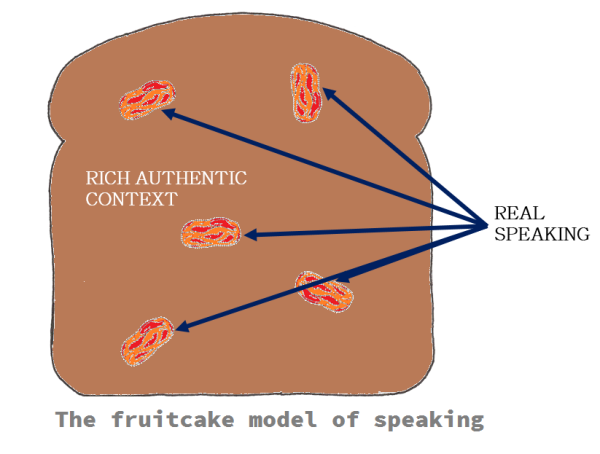

For speaking to have meaning, it must be situated in real, authentic, appropriate contexts; contexts that are familiar to the child. Speaking about democracy and freedom at this stage of development is too abstract. Children’s speaking should be focused on what is relevant and meaningful; that which carries meaning for the child in his or her everyday experience. Childspeak must be situated in, around and inside of real, rich, authentic contexts that are motivating to the child. It is only then that we will experience real speaking for meaning. Here at the Extraordinary Learning Foundation, we have summarised this idea with the following diagram – the fruitcake model of speaking:

I am speaking to Haneck von Beer about his approach to speaking for meaning with his Grade 4 class. Haneck works at the Grunig Institute and it is the lunch recess. All of Haneck’s class have eaten their lunch and are out exploring their ideas in the imaginarium resources area.

“There’s this kid, George,” Explains Haneck, “All he ever wanted to talk about was planets and space and yet he has no direct experience of these concepts.”

This is, indeed, a common problem.

Haneck continues, “And so I asked him whether he had any pets.”

I smile, I can see where this is going and how the principles of the fruitcake model will apply.

“George says that he has a cat,” Continues Haneck.

I nod.

“So I ask him to talk about his cat. For the first time, I heard George speak in a real, authentic, appropriately situated, meaningful way.” Haneck smiles.

If only all educators had such skills! “What did George say?” I ask, totally subsumed in this moment of genuine authenticity.

“He said, ‘I have a cat and it is brown’.”